Byline By: Nestor P. Burgos Jr.

Inquirer Visayas

12:41 AM July 26th, 2014

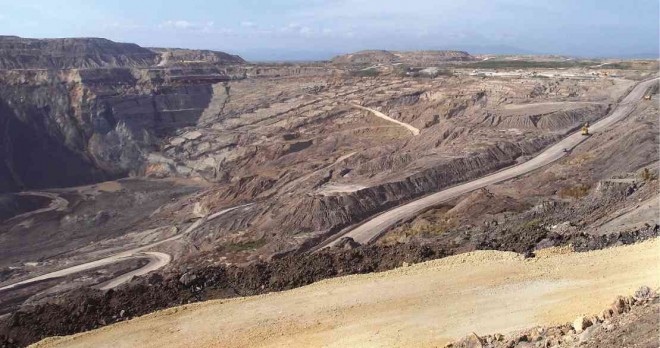

FIVE workers died and five others went missing when a portion of the western wall of the Panian open-pit coal mine on Semirara Island collapsed on Feb. 13 last year. NESTOR P. BURGOS JR

Danilo Domingo, 58, has been living all his life in Barangay Tinogboc on Semirara Island. Now, he fears for the future of his children and their island.

“Our mangroves, sea grass and other marine resources are fast diminishing. There might be nothing left when the mining ends,” he told the Inquirer.

In a forum on the impact of mining operations on Antique province, Domingo and other Semirara residents pleaded for assistance from government agencies and environmental advocates to help them cope with the effects of coal mining on their island’s marine resources and the alleged dislocation of residents.

“Government agencies should strictly monitor and ensure the implementation of environmental rules and regulations,” said Domingo, head of Bolo Fisherfolk Farmers Association.

He cited a study conducted by researchers tapped by Pambansang Kilusan ng mga Samahang Magsasaka showing that 31 of the 35 mangrove species in the country are existing on Semirara Island.

But the study, based on satellite images using Google Earth’s time slider, showed that mangrove areas on the island dropped from 427.92 hectares in 2009 to 344 ha in 2014 or a decrease of 83.92 ha.

“Many mangrove areas have been filled in,”Domingo said.

The forum, jointly organized by nongovernment organizations with the support of the British Embassy in Manila, was attended by representatives of the Commission on Human Rights, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and the Department of Energy (DOE).

The municipal government of Caluya, Semirara Mining Corp. (SMC) and the office of Antique Gov. Exequiel Javier did not send representatives to attend the forum despite being invited by the organizers.

The Inquirer repeatedly called and sent text messages to Juniper Barroquillo, SMC administrative officer, but he did not respond.

For two weeks, the Inquirer also tried to reach lawyer John Sadullo, SMC vice president for legal affairs, but he was either out of his office or on sick leave. His office did not return calls nor sent a statement despite repeated requests.

But the company has in the past repeatedly denied allegations of environmental violations causing pollution on the island.

On its website, SMC said its reforestation team had planted

1.2 million trees on the island from 2000 to 2012. It had planted mangroves on a 172-hectare area by 2012.

The abandoned and barren Unong mine is being rehabilitated and planted with trees to stabilize the soil. The mine pit that is now filled with water hosts eels, tilapia and other fish and is being developed into an eco-tourism site, according to the SMC website.

Retired Energy Undersecretary Ramon Allan Oca, who has extensive knowledge of the SMC operations, said the company had met international environmental, safety and quality standards.

He said the operations and environmental impact were regularly being evaluated by the Multipartite Monitoring Team (MMT). The MMT, composed of representatives of SMC, the DENR and the community, is tasked to ensure that regulations and conditions of the environmental compliance certificate are followed.

Since mining operations started in Semirara in 1977, Domingo has seen the island become one of Asia’s biggest coal mines. Semirara is among a group of nine islands comprising Caluya town in Antique. Semirara is composed of three villages (Semirara, Tinogboc and Alegria).

SMC, owned by DMCI Holdings Inc., is the country’s biggest domestic producer of coal, accounting for 7,570,003 metric tons of the total 7,842,409 MT produced locally in 2013, according to data from the coal division of the DOE.

SMC took over the then government-owned Semirara Coal Corp. in 1999. In 2011, it posted a P6-billion profit.

The company employs some 2,800 employees with about 4,000 people relying on its operations for livelihood.

Mining is the biggest source of income of Semirara village, which hosts SMC’s Panian mining pit, and Caluya municipality.

The internal revenue allotment of Semirara village reached P225 million in 2012 while Caluya municipality had a royalty share of P290 million.

But Domingo said the island and the people were paying a high price.

Despite massive earnings from coal production, the lives of people especially in Tinogboc and Alegria have not significantly improved, he said.

He cited unpaved roads, lack of infrastructure, absence of a hospital with adequate personnel and facilities, and the absence of a decent pier.

Provincial Board Member Errol Santillan admitted at the forum that even he, a provincial official, does not have adequate information about the situation on the island.

“The island is too far from the provincial center, and we hardly get any information. We were not even consulted on the [DOE’s] approval to extend and expand the operations of SMC,” he said.

In 2008, the DOE extended SMC’s coal operating contract (COC) by another 15 years or up to 2027. The original

35-year COC was supposed to expire in 2012.

The COC gives exclusive right to SMC to explore, develop and mine for coal on Semirara Island.

The DOE in 2009 also expanded the coverage of the COC from the original 5,500 ha in Semirara to 12,700 ha, including 3,000 ha in Caluya, the main island, and 4,200 ha on Sibay Island.

Santillan urged the DENR to study possibilities of declaring other areas in Caluya and Antique as environmentally protected areas and off limits to mining exploration and extraction, citing the rich and diverse marine resources on the island.

“If we cannot stop the existing mining operations, let us limit them, especially in areas where people are relying on marine resources for their livelihood,” he told the Inquirer. source

No comments:

Post a Comment